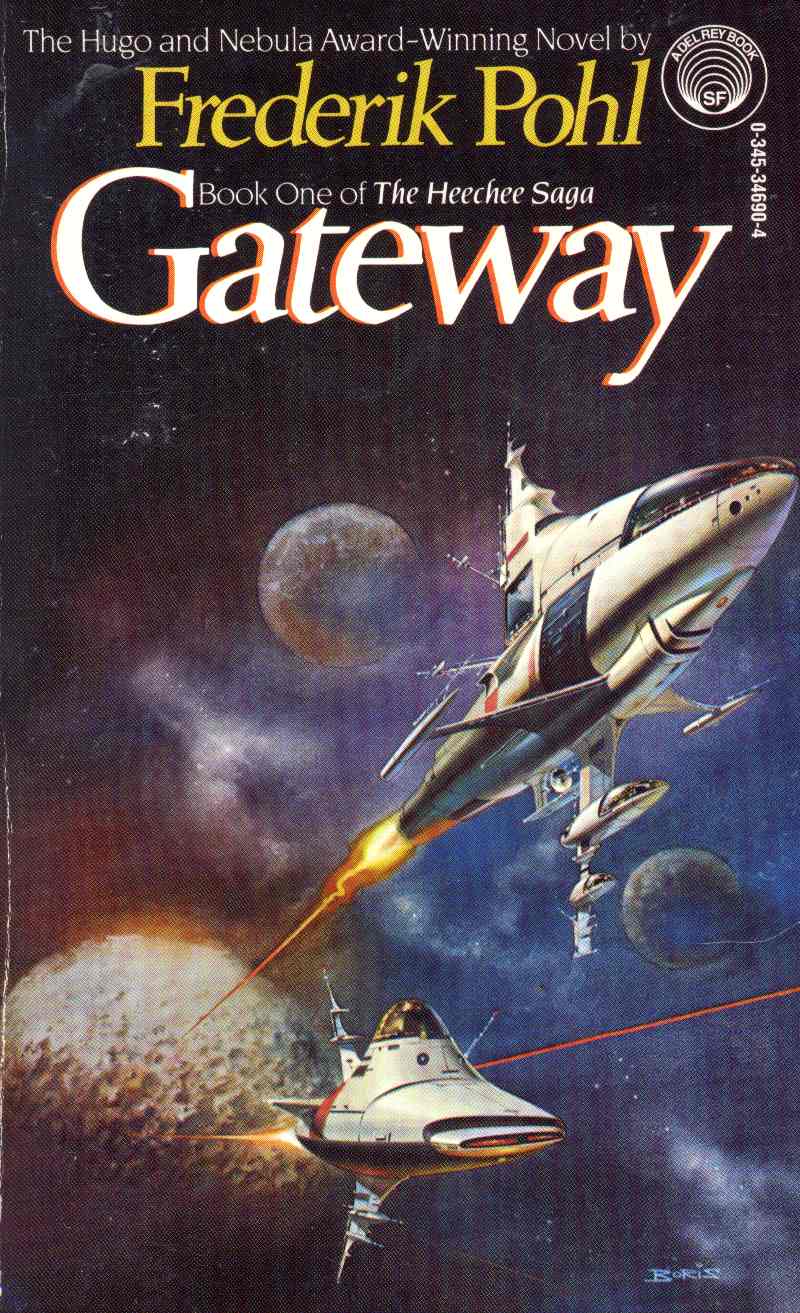

Frederik Pohl

1977

Awards: Nebula, Hugo, Campbell, Locus

Rating: ★ ★ ★ – –

The best thing about Gateway is

the unique setting and very cool premise. And Pohl explores that setting and that premise with a

story line that is interesting enough that it doesn't seem like it

was created half-heartedly just to show off the universe he invented.

It is the relatively near future. During our exploration of nearby

space, we have discovered a spaceport, which we have named "Gateway," which was

been abandoned long ago by an alien species, who we have named the "Heechee."

The Heechee were highly technologically advanced and left behind an array of

valuable artifacts at Gateway, including spaceships with the capability for

hyperspace travel. There are many of these ships still fueled up and

docked at the spaceport’s gates. Everything is in perfect working order.

It is like the Heechee just up and left one day, leaving everything

intact and running.

This discovery is a boon for mankind. And, conveniently, the Heechee appear to have been about our size and to have

had similar environmental requirements as us, so it is possible for us to use

their station and their ships in relative comfort.

The only catch is that we can’t read any of their instruction manuals or

any of the indicators on any of their equipment. Everything we know

about their technology we have learned from brute force experimentation –

by getting into the ships, pressing a bunch of buttons, and seeing

what happens.

We have learned some very basic things. We have figured out how to select a

destination code and to start the ships on their journey. We know that once

the ship is started, it will not deviate from its pre-programmed course

and it will automatically return to Gateway on its own.

But we don’t know what the vast majority of the destination codes stand for. So most of the time we don’t know where the ship is going. We don’t know

how to program it to turn around or go somewhere else while it is in

flight. We don’t know how to tell how long the voyage is going to be.

And we don’t know whether or not the ship actually has enough fuel to

get there.

So an industry has grown up around Gateway in which a corporation hires

people to risk their lives flying the Heechee ships to where ever the

ships might take them, and then gives them a share of the profits if

they (a) survive the trip and (b) find something that is useful to the company.

Sometimes the ships end up in the middle of a supernova. Sometimes they

run out of fuel and never come back. Sometimes the ships return with a

dead crew whose food or oxygen ran out before the trip was over.

But sometimes the ships take the crew to a brand-new planet that is

habitable or has a supply of valuable ore. Sometimes it takes them to a

new Heechee port with still more artifacts. And sometimes the trip gives

us more of a clue to the navigation system. When anything like that

happens, it makes the lucky crew on that ship very wealthy.

The main character, Bob Broadhead, is one of these Gateway pilots. His first two missions were small and uneventful. His third mission made him wealthy

beyond his wildest dreams, but left him a traumatized wreck with guilt

and nightmares that he can’t get rid of.

The book starts with Broadhead in therapy (with a computerized therapist he calls Sigfrid von Shrink)

after this third mission. Through flashbacks and sessions

with Sigfrid, we learn first about Gateway and the Heechee, and then gradually what

happened to Broadhead to make him both so wealthy and so messed up.

The best part of the book is the core premise: the

Gateway spaceport and the ships that can set people up for life or kill

them in any number of horrible ways. I also found it interesting to try to put together a picture of the Heechee from the stray bits that pilots discover here and there.

Broadhead himself is not a terrifically inspiring character, however. And the story is not tremendously strong or arresting; it was adequate, but it was mainly the strength of the premise that carried my interest through to the end of the book.

And I do have to admit that although I can see that Broadhead’s third mission

was scientifically very important, I don’t understand why it was of

concrete monetary value to a corporation.

An earlier version of this review originally appeared on Cheeze Blog.

No comments:

Post a Comment