Cory Doctorow

2008

Awards: Campbell

Nominations: Nebula, Hugo

Rating: ★ ★ ★ ★ –

MINOR SPOILER ALERT

Little Brother is a story about hackers. But it is not a cyberpunk novel. It is about innocent humans targeted by a repressive police state, fighting for their civil rights, their freedom, and sometimes their lives.

Yes, the main character, Marcus Yallow, has a wry, cocky, hacker-appropriate attitude. And, yes, he does lots of hacking, in which he uses real hacker techniques to burrow into the tightest security systems, and the techniques don’t come off as cheesy as they so often do in works of fiction. But Marcus’ unwarranted arrest, and the way U.S. government officers treat him while he is in their custody, and the way he is mercilessly hounded even after he is set “free,” are far from the world of cocky hacking, and very scary.

Marcus is a seventeen-year-old high school student living in San Francisco. He is irreverent and smart, mainly using his hacking skills for fun.

One day, Marcus and his friends cut class, as they often do, to join a live-action adventure game. Unfortunately, they happen to be out on the street with no legitimate excuse and a bunch of suspect-looking technology when terrorists attack the city. The group of friends are swept up in the Homeland Security crackdown that follows and are thrown into a secret prison, given no food or bathroom, hog-tied with zip cuffs, and interrogated with all the force the DHS has to muster.

When Marcus at first refuses to unlock his phone they accuse him of being a terrorist, torture him, and then leave him soaking in his own urine for hours. Eventually, he cracks—as the vast majority of us would—and agrees to give them all his passwords if they will just let him go home. They let him go, but they stay on his tail, threatening to bring him in again for good if he strays off the path of correct behavior.

Their degrading, dehumanizing treatment terrorizes and cows Marcus, and that fear stays with him. But gradually his fighting spirit comes back, too. His outrage grows as the security crackdown gets harsher and DHS surveillance gets more widespread and insidious. And, as time passes, one of his friends still is not released by DHS, and may be, for all he knows, dead.

Marcus decides he has to bring down the people who tortured him and his friends. He discovers that DHS has (clumsily) bugged his laptop, so he hacks his internet-enabled Xbox and turns it into a secure communication device, and spreads the Xbox crack code to his friends, eventually turning the Bay Area into a network of under-20-something hackers and gamers called “the Xnet” that are ready to help tear down the repressive regime with him: a scattered, disorganized, and passionate virtual army.

When the police and DHS become aware of the Xnet, they use it as an excuse to increase their strategy of harassment and surveillance. They send spy vans and helicopters roaming throughout the city, looking for Xbox signals; they track every person’s movements around the city through the RFID chips in their Muni and toll passes; and they install facial recognition cameras everywhere. Whenever someone is determined to have an “unusual” pattern of movement, they are questioned and intimidated.

In spite of all of this, the vast majority of the adult population are okay with having every one of their movements—online and off—tracked, recorded, and analyzed by authorities. This is one of the most frustrating and realistic parts of the book. Yes, it is inconvenient and can be annoying, they say, but it is all to keep us safe. If you aren’t doing anything wrong, you shouldn’t have anything to worry about.

And the mainstream media does nothing to change that opinion, reporting on everything with a security bias—so, for example, a concert where a bunch of kids are beaten and gassed by police is reported as a “riot” started by the concert-goers. Even Marcus’ parents are convinced that these measures are there for a good reason, even as kids (and, increasingly, sympathetic adults) get pepper-sprayed, arrested, and subjected to “questioning” (a.k.a. torture, including waterboarding).

Ironically, the actual terrorists continue to escape justice, while more and more innocent people are bullied and jailed. Thousands of people are swept up in this security farce as DHS tactics grow more intense. And Marcus and his legions of Xnetters engage in steadily more confrontational hacks and actions—with varying amounts of success—until Marcus is finally face to face with his torturers once again.

Technically, Little Brother has a happy ending. But it also makes it clear that any victory for justice is always a temporary one, and that the defense of civil rights is a constant fight. The authoritarian forces that would ask us to give up our liberty in the name of security are always there, waiting for the least crack in our will to creep back in. Marcus and the hackers and the lawyers and the teachers and the reporters must remain ever vigilant to make sure it never happens again.

Part of the reason this book works so well is that Marcus’s hacker techniques are all completely authentic. The social engineering methods to discover passwords; the conduct of ultra-secure conversations by tunneling through DNS; the “borrowing” of RFID chip signatures from innocent bystanders nearby—all of those are real. And even though these techniques can be complicated, Doctorow explains them clearly and understandably without being superior or silly. He’s clearly someone who knows what he’s talking about (a fact backed up by the fact that he has hackers and security experts writing his afterwords).

Doctorow and his afterword writers also explain why hacking is necessary, and actively encourage his readers to think about how to hack things. For one thing, it’s fun. For another, it’s educational; you learn how things work. And for another, when you publicly expose security flaws, you make people have to tighten up their security, making security stronger. There’s no way to make systems as secure as they can be without testing their limits.

The other, more important reason that Little Brother is powerful (and anxiety-producing) is because it is set in a surveillance state that is very much real life. Doctorow wrote this book at the end of George W. Bush’s presidency, when that administration was actively demolishing civil rights in the name of protecting us from terrorists, and doing it with the unquestioning support of most of the populace and mainstream media. It was very relevant then, and is, unfortunately, even more relevant now.

It’s a dangerous book, too, because Doctorow calls into question all the things we have had to adjust to following the formation of the DHS: increased x-ray screenings, ID checks, taking your shoes off at the airport. All of which, he says, are actually pointless in actually preventing anything from happening. These tactics are less about actually catching criminals and more about keeping a population intimidated and fearful so that they can be more easily manipulated.

The main question this book raises is, I think, one of the most important of our time: when you are faced with an unjust, militaristic, authoritarian regime, how do you respond? Do you keep your head down, trying to keep yourself and your family safe, and hope it gets better on its own? Or do you fight back, risking your liberty and possibly your life?

It’s critical to think about this now that the U.S. is faced with the most schizophrenic, authoritarian regime I’ve seen in my lifetime. I know what I’d like to think I would do. But I don’t honestly know how far I’d be willing to go if my life was at stake.

Showing posts with label Virtual Reality. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Virtual Reality. Show all posts

Friday, May 5, 2017

Friday, January 15, 2016

Book Review: Permutation City

Greg Egan

1994

Awards: Campbell

Rating: ★ ★ – – –

What Egan is trying to do in Permutation City is to examine a large and diverse array of issues related to the virtualization of human life. He uses his various characters to explore whether you can achieve immortality as a virtual copy of yourself and what that would be like; whether it would be possible to create life forms that could actually evolve in a virtual environment; the mental adjustments that you might go through upon waking up and discovering that you are a virtual copy of your former self; how economic inequality might affect your virtual existence; and even what a virtual hell might be like.

What Egan is trying to do in Permutation City is to examine a large and diverse array of issues related to the virtualization of human life. He uses his various characters to explore whether you can achieve immortality as a virtual copy of yourself and what that would be like; whether it would be possible to create life forms that could actually evolve in a virtual environment; the mental adjustments that you might go through upon waking up and discovering that you are a virtual copy of your former self; how economic inequality might affect your virtual existence; and even what a virtual hell might be like.

All of this is pretty ambitious. And some of the specific scenes are certainly thought-provoking and vividly written. But the main story line is not at all compelling, leaves many more promising smaller story lines unfinished, and is based on a vaguely explained metaphysical theory with feeble conceptual underpinnings. It seems as if Egan first brainstormed all of the virtual reality theories he could think of, and then just connected them all together with the thinnest and stretchiest of story skins.

In the world of Permutation City, in 2045, people can create fully sentient electronic copies of themselves, with memories intact. These “Copies” live in virtual environments but can interact with flesh-and-blood humans through immersive interfaces. People can extend their lives a long time this way; for example, many major companies are still being run by virtual Copies of their founders, many years after the originals have died.

There is a catch, though: creating a Copy of yourself is expensive. And the processors required to run your Copy and its virtual environment are expensive too, and usually require a trust be set up to fund them in perpetuity. So self-virtualization is really only available to the wealthy. And less wealthy Copies running on cheaper processors can be stuck living at speeds many times slower than real time, making it hard for them to interact with other, faster Copies, and next to impossible to interact with the outside world.

The economic inequality of processor speed for virtual humans could be an interesting plot in itself. Egan creates, for example, a radical separatist movement among Copies, “Solipsist Nation,” which advocates turning entirely inward to your virtual self and cutting yourself off completely from the “real” outside world. And some equality-minded faster Copies, particularly those in Solipsist Nation, like to go “slumming” at slow-down bars, where all of the Copies in the bar sync themselves down to the speed of the lowest person there. But these are only incidental topics, dealt with only briefly; in fact, the only two characters in the book who talk about these issues are dead ends with almost no bearing on the main story line whatsoever.

No, the main narrative instead centers on the crackpot theories of main character #1: Paul Durham, insurance salesman by profession and virtual reality experimentalist by passion, who claims to have been reincarnated from dust twenty-three times.

Durham likes to create Copies of himself to experiment with, to analyze his reactions to being virtualized. The book opens, in fact, with a scene of one of his Copies waking up and realizing that he is virtual, not a flesh-and-blood human. The Copy goes through shock, depression, panic, and then anger as he realizes that the fail-safes in his environment won’t allow him to commit virtual suicide.

This scene is one of the best in the book, and the issues it raises might have been enough to hang the entire plot on. It brings up good questions, such as: if everything feels real around me, but I know it isn’t real, does it make a difference? Should it? What kind of life could I build for myself in a virtual world? Does it make me less of a person to be virtual? How do I go about accepting who I am?

But rather than musing over these questions for long, Durham’s Copy quickly starts to accept his situation. And, sitting there in his unique environment, he comes up with a theory, which he calls the “dust theory,” that goes like this:

Durham theorizes further that he can use this wackjob theory to create a virtual refuge for Copies that is completely unconnected and protected from the real world. He thinks that if he builds the seed of this environment correctly, loads a bunch of Copies into it, launches it into the void, and then cuts it off from the outside world, that it will continue functioning, and even growing, forever. It won’t need any physical presence in our universe at all, so it won’t be subject to real-world competition for power or processors, or the potential of being shut down.

To provide ethically questionable entertainment that could last potentially forever for the residents of his refuge, Paul then enlists the help of main character #2, Maria Deluca. Deluca is a hobbyist who spends much of her free time playing with virtual bacteria in a bacterium-modelling virtual universe, and she has recently become the first person ever to develop a virtual bacterium that actually evolves and adapts to its environment.

On what I might uncharitably say is the thinnest of premises to include another not-fully-realized virtual-reality-related thought experiment in the book, Durham hires Deluca to build the seed of an entirely new planetary system, running separate from but parallel to the human Copies’ refuge. This alien environment will be packed with the building blocks of virtual life, designed to grow and evolve into a fully diverse ecosystem of its own, for the Copies to observe. (This is another subplot that might have been good as the fully-developed center of a novel of its own: following the alien ecology’s evolution in detail, interacting with the inhabitants, answering their questions about their creation, coping with the moral issues it raises. But this was not to be.)

Durham then goes out and recruits a bunch of wealthy Copies to fund the project. One of these is Thomas Riemann, who, unbeknownst to anyone living today, long ago in his dark youthful past, semi-accidentally killed his girlfriend. The murder continually weighs on his conscience, and he runs through the incident in his mind over and over again. (Riemann’s agony, too, might have been good explored as a story by itself: how prolonging your life through virtualization doesn’t rid you of your past mistakes, and how it can even turn an infinite lifespan into a sort of hell. Egan deals with this a bit, but then lets it fizzle out.)

Durham and Deluca set up the seed for the standalone environment, which they are calling Elysium, pack it full of billionaire client Copies and the seed of Deluca’s virtual alien planet, and launch it out into the ether.

And it turns out that the dust theory works, that the Copies survive, that Elysium works, that Deluca’s alien world works, and that it all keeps growing and expanding and evolving, unconnected from the real world they left behind.

And then, thousands of years later, Elysium is faced with a new crisis, when the alien planet has developed sentient life forms and the two environments appear to be affecting each other, encroaching on each other.

Permutation City certainly has some bright spots: isolated subplots with potential, isolated sections with interesting narratives. But the main story is flat and almost emotionless with the barest excuse for a rationale, and the subplots are stuck into it haphazardly. In general, it does a lot of metaphysical navel-gazing about esoteric virtual reality theories without blending them into a coherent whole—much less an exciting story.

1994

Awards: Campbell

Rating: ★ ★ – – –

What Egan is trying to do in Permutation City is to examine a large and diverse array of issues related to the virtualization of human life. He uses his various characters to explore whether you can achieve immortality as a virtual copy of yourself and what that would be like; whether it would be possible to create life forms that could actually evolve in a virtual environment; the mental adjustments that you might go through upon waking up and discovering that you are a virtual copy of your former self; how economic inequality might affect your virtual existence; and even what a virtual hell might be like.

What Egan is trying to do in Permutation City is to examine a large and diverse array of issues related to the virtualization of human life. He uses his various characters to explore whether you can achieve immortality as a virtual copy of yourself and what that would be like; whether it would be possible to create life forms that could actually evolve in a virtual environment; the mental adjustments that you might go through upon waking up and discovering that you are a virtual copy of your former self; how economic inequality might affect your virtual existence; and even what a virtual hell might be like. All of this is pretty ambitious. And some of the specific scenes are certainly thought-provoking and vividly written. But the main story line is not at all compelling, leaves many more promising smaller story lines unfinished, and is based on a vaguely explained metaphysical theory with feeble conceptual underpinnings. It seems as if Egan first brainstormed all of the virtual reality theories he could think of, and then just connected them all together with the thinnest and stretchiest of story skins.

In the world of Permutation City, in 2045, people can create fully sentient electronic copies of themselves, with memories intact. These “Copies” live in virtual environments but can interact with flesh-and-blood humans through immersive interfaces. People can extend their lives a long time this way; for example, many major companies are still being run by virtual Copies of their founders, many years after the originals have died.

There is a catch, though: creating a Copy of yourself is expensive. And the processors required to run your Copy and its virtual environment are expensive too, and usually require a trust be set up to fund them in perpetuity. So self-virtualization is really only available to the wealthy. And less wealthy Copies running on cheaper processors can be stuck living at speeds many times slower than real time, making it hard for them to interact with other, faster Copies, and next to impossible to interact with the outside world.

The economic inequality of processor speed for virtual humans could be an interesting plot in itself. Egan creates, for example, a radical separatist movement among Copies, “Solipsist Nation,” which advocates turning entirely inward to your virtual self and cutting yourself off completely from the “real” outside world. And some equality-minded faster Copies, particularly those in Solipsist Nation, like to go “slumming” at slow-down bars, where all of the Copies in the bar sync themselves down to the speed of the lowest person there. But these are only incidental topics, dealt with only briefly; in fact, the only two characters in the book who talk about these issues are dead ends with almost no bearing on the main story line whatsoever.

No, the main narrative instead centers on the crackpot theories of main character #1: Paul Durham, insurance salesman by profession and virtual reality experimentalist by passion, who claims to have been reincarnated from dust twenty-three times.

Durham likes to create Copies of himself to experiment with, to analyze his reactions to being virtualized. The book opens, in fact, with a scene of one of his Copies waking up and realizing that he is virtual, not a flesh-and-blood human. The Copy goes through shock, depression, panic, and then anger as he realizes that the fail-safes in his environment won’t allow him to commit virtual suicide.

[Note here to the editor of Permutation City: the term that Egan uses to describe committing virtual suicide—when Copies can’t cope with being virtual and turn themselves off permanently—is “baling out.” He uses this term repeatedly. Unless he is making some clever pun on the word “bale,” as in “baleful,” I think he meant to use the term “bailing out,” which means to remove yourself from a harmful situation. If it is indeed not a pun, then it is misspelled in the text, over and over and over.]Durham’s Copy’s frustration is understandable. The thought processes he goes through and the feelings he has, when he thinks about how he can no longer touch his girlfriend or walk beyond the borders of his virtual world, ring very true. He knows he could simulate those things, but they wouldn’t be real, and that is tremendously depressing to him at first. He knows that the simulation of his virtual world disappears when it is out of his eyesight, that none of the visuals are generated by the computer until they need to be generated to protect his illusions; he wishes he could turn his head fast enough to see the parts that aren’t there.

This scene is one of the best in the book, and the issues it raises might have been enough to hang the entire plot on. It brings up good questions, such as: if everything feels real around me, but I know it isn’t real, does it make a difference? Should it? What kind of life could I build for myself in a virtual world? Does it make me less of a person to be virtual? How do I go about accepting who I am?

But rather than musing over these questions for long, Durham’s Copy quickly starts to accept his situation. And, sitting there in his unique environment, he comes up with a theory, which he calls the “dust theory,” that goes like this:

Everything is made of tiny cosmic particles, or what Durham’s Copy calls “dust.” If there are sentient beings in that dust, their very beingness—or, as he says, “the internal logic of their experience”—is strong enough that if they are somehow destroyed, that the particles that made them up will still combine in an infinite set of permutations that eventually will result in them coming into existence again.

Durham theorizes further that he can use this wackjob theory to create a virtual refuge for Copies that is completely unconnected and protected from the real world. He thinks that if he builds the seed of this environment correctly, loads a bunch of Copies into it, launches it into the void, and then cuts it off from the outside world, that it will continue functioning, and even growing, forever. It won’t need any physical presence in our universe at all, so it won’t be subject to real-world competition for power or processors, or the potential of being shut down.

To provide ethically questionable entertainment that could last potentially forever for the residents of his refuge, Paul then enlists the help of main character #2, Maria Deluca. Deluca is a hobbyist who spends much of her free time playing with virtual bacteria in a bacterium-modelling virtual universe, and she has recently become the first person ever to develop a virtual bacterium that actually evolves and adapts to its environment.

On what I might uncharitably say is the thinnest of premises to include another not-fully-realized virtual-reality-related thought experiment in the book, Durham hires Deluca to build the seed of an entirely new planetary system, running separate from but parallel to the human Copies’ refuge. This alien environment will be packed with the building blocks of virtual life, designed to grow and evolve into a fully diverse ecosystem of its own, for the Copies to observe. (This is another subplot that might have been good as the fully-developed center of a novel of its own: following the alien ecology’s evolution in detail, interacting with the inhabitants, answering their questions about their creation, coping with the moral issues it raises. But this was not to be.)

Durham then goes out and recruits a bunch of wealthy Copies to fund the project. One of these is Thomas Riemann, who, unbeknownst to anyone living today, long ago in his dark youthful past, semi-accidentally killed his girlfriend. The murder continually weighs on his conscience, and he runs through the incident in his mind over and over again. (Riemann’s agony, too, might have been good explored as a story by itself: how prolonging your life through virtualization doesn’t rid you of your past mistakes, and how it can even turn an infinite lifespan into a sort of hell. Egan deals with this a bit, but then lets it fizzle out.)

Durham and Deluca set up the seed for the standalone environment, which they are calling Elysium, pack it full of billionaire client Copies and the seed of Deluca’s virtual alien planet, and launch it out into the ether.

And it turns out that the dust theory works, that the Copies survive, that Elysium works, that Deluca’s alien world works, and that it all keeps growing and expanding and evolving, unconnected from the real world they left behind.

And then, thousands of years later, Elysium is faced with a new crisis, when the alien planet has developed sentient life forms and the two environments appear to be affecting each other, encroaching on each other.

Permutation City certainly has some bright spots: isolated subplots with potential, isolated sections with interesting narratives. But the main story is flat and almost emotionless with the barest excuse for a rationale, and the subplots are stuck into it haphazardly. In general, it does a lot of metaphysical navel-gazing about esoteric virtual reality theories without blending them into a coherent whole—much less an exciting story.

| ||||||

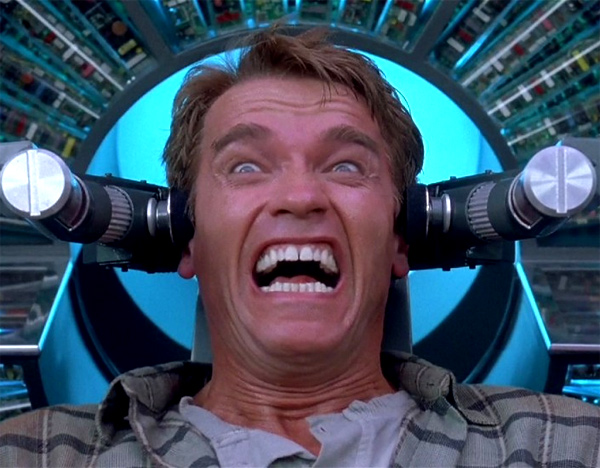

| Arnold Schwarzenegger in Total Recall |

I should say here that it is possible

to incorporate questions about perception and virtual reality into riveting

stories. Take, for example, maybe half of the works of Philip K. Dick. Dick

may have done such a good job of it because he was genuinely afraid of not

being able to distinguish between reality and artificial memories, and he let

his real fear come through into his writing.

Friday, August 14, 2015

Book Review: Genesis

Poul

Anderson

2000

Awards:

Campbell

Rating:

★ – – – –

I

don’t know what the Campbell Award judges were thinking when they read this

book. Genesis is a confused, undeveloped,

sometimes pretentious story that veers from one partially-formed idea to

another in a style akin to that of Vernor Vinge. The one advantage that this

book has over Vinge’s novels is that it is relatively short.

I

don’t know what the Campbell Award judges were thinking when they read this

book. Genesis is a confused, undeveloped,

sometimes pretentious story that veers from one partially-formed idea to

another in a style akin to that of Vernor Vinge. The one advantage that this

book has over Vinge’s novels is that it is relatively short.

The

main character in Genesis is

Christian Brannock, a man from near-future Earth. As a boy, Brannock dreams of discovering

life in other star systems. As an adult, he finds work building transmission

towers on Mercury; there he works with a semi-intelligent robot, Gimmick, with

whom he is connected mentally, and the two of them come just shy of sharing a real

consciousness. By the time Brannock reaches old age, Earth’s massive global computer

network has acquired sentience. And when Brannock is about to die, because he had

worked so closely and successfully with Gimmick, the sentient global computer

network invites Brannock to upload his consciousness into it so that he can

live essentially forever, virtually, as a part of its AI brain.

The

sentient global computer network then somehow acquires the capability to spin

off nodes of itself to do multiple separate assignments simultaneously, and to transport

itself and its nodes anywhere at will. It spreads its nodes far and wide across

the galaxy and the nodes take copies of Brannock’s consciousness with them as

they go. Over many millennia, the virtual Brannock is able to observe and

record thousands of different stars and planets—just what he dreamed of as a

boy.

Finally,

after several million years of exploration, the virtual Brannock gets bored and

asks to be shut down. Instead of shutting him down, though, the central computer

consciousness gives him a new assignment: go back—in physical form—and check on

Earth. By this time, Earth is only about a hundred thousand years from being

sizzled by its enlarging sun. And “Gaia,” the node of the galactic central

brain that was left behind to protect Earth, has been behaving weirdly: her

reports are getting more confusing and abrupt, and she doesn’t appear to be

doing anything about protecting Earth from its impending sizzling.

The

plot that I’ve just described is all basically fine. It’s everything about the

rest of the book that is problematic.

For

one thing, over the years that Brannock’s consciousness explores the galaxy, we

get bits and snatches of what is happening back on Earth in the form of little periodic

vignettes of human adventures. Only one of these vignettes is even semi-connected

to the main story line, so they seem scattered and hodge-podge. It feels like Anderson

had some random short stories that he wasn’t sure what to do with, so he just stuck

them into this book where ever he thought they would fit.

For

another thing, the writing is a bit pretentious; Anderson likes to use words

like “sunsmitten,” “coolth,” and “laired” and is not able to make them sound

natural. His descriptions are also unhelpfully poetically vague, especially at

dramatic moments of tension when we most need him not to be poetic and vague. Most

of the time, all he gives us is flashes of light and snatches of things almost

seen. At one point when Gaia attacks Brannock’s aircraft, Anderson describes it

thus: “Arcs leaped blue-white. Luminances flared and died. Power output

continued; the aircraft stayed aloft…the dance of atoms, energies, and waves

went uselessly random.”

Another conflict with Gaia is pretty much just described as “strife

exploded.”

And

for another thing, what happens after Brannock reaches Earth seems

unnecessarily convoluted and pointless. He splits into two parts: Brannock the

A.I, which takes the physical form of a metallic robot, and Christian the man emulation,

which takes the physical form of a human. (Maybe—or maybe Christian the man

emulation is just a virtual copy of a man in a virtual environment. It’s not

really clear, as it’s also unclear why he needed to split into two parts in the

first place).

Brannock

the metallic robot goes off to explore Earth’s surface. There he has his own

little adventure, meeting up with the few humans who remain on Earth and trying

to find a way to contact his home central computer core and tell it about Gaia,

who, at this point, has gone completely off her rocker and is trying to kill

him. It’s unclear where the home central computer core is in all of this, and

why it couldn’t find out itself what is going on with Gaia, and why the core is

not still on Earth since that’s where it all started anyway, and why Gaia is

just a node and not the center of the galactic AI brain.

Meanwhile,

Christian the man emulation goes off into some kind of maybe real, maybe

virtual environment in which he meets Laurinda, the consciousness of a woman

who was uploaded into Gaia long ago just like Christian was uploaded into the central

galactic brain. Christian and Laurinda discover that Gaia has been running

experiments, recreating various times in history and then letting them play

out, to see how history might have wound up differently with different starting

parameters. They take tours of the different scenarios, to try to see what Gaia

is up to, and are horrified because as soon as Gaia determines that a given

scenario is not going to result in the outcome she wants, she destroys it. But

it is unclear to me why Laurinda doesn’t know all this already, since she’s a

part of Gaia’s consciousness, and whether the scenarios are virtual or real,

and if they’re real, where the heck are they stored and how she's able to get Christian's and Laurinda's hair and costumes to be chronologically appropriate instantly, and if they’re virtual, why Christian

and Laurinda are so horrified at the scenarios’ destruction, since they’re not real.

It’s

also unclear what Gaia hopes to gain from these experiments. At one point, Laurinda

says that it seems like Gaia is trying to create a “genuinely new form of

society.” What does that mean? Why is she trying to create it? What is she

going to do when she gets it? If it’s virtual, what’s the point? And if it’s

real, where is she going to put all the people in her simulation if she refuses to protect Earth from destruction?

Anyway,

eventually Christian, Brannock, and Laurinda have to try to stop Gaia from

doing her experiments but by then I’d long since stopped caring. And I never

really got answers to any of my questions

There

are many directions that Anderson could have

developed more in this book, any of which would have provided good fodder for thought-provoking

fiction. But instead it felt haphazard and undeveloped—like he was making it up

as he went along.

Friday, June 5, 2015

Book Review: Fahrenheit 451

Ray

Bradbury

At

this point, Montag knows he can never go back to his job. He is

so distraught at having to question everything that he has taken for granted that he makes a series of bad missteps, from showing his wife and

her friends his books to getting in contact with a member of the book-saving

underground. And when the firemen finally show up at his own house, Montag knows he’s

in deep trouble.

~

1953

Awards:

Retro Hugo

Rating:

★ ★ ★ ★ –

Fahrenheit 451 is about a man, Guy

Montag, who is a fireman. In Montag’s time, many years in the future from ours,

it is illegal to read books. And the job of a fireman is not to put out fires,

but to burn any books he finds.

The

reason that books are illegal (we hear from Montag's boss, the Fire Chief) is that books make people unhappy. Books can be

violent, melancholic, confusing, requiring of deep thought, and full of

different philosophies and conflicting ideas that require hard work to reconcile. This makes people confused and upset. By

burning the books, firemen are standing guard against societal unhappiness.

To

make themselves even more constantly happy, people have also surrounded themselves

with distracting stimuli in their homes, businesses, and subways. Everywhere

they go they are assaulted by advertisements, jingles, and empty, content-free virtual

reality dramas. Left with nothing but vapid entertainment and an absence of introspection

or critical thought, society has become almost sociopathic. Suicide, murder, and

drug overdoses are common. People think nothing of hitting animals and even

people while they are driving.

At

the beginning of the book, fireman Montag loves his job; he gets a ridiculous

grin on his face as books turn into ashes. He enjoys having a respected place

in his community. And he thinks he has a perfectly fine relationship with his

wife Mildred.

But

one day on the way home from work he meets a girl, Clarisse, and her conversation

is so radically different from what he’s used to that it sets him off balance.

Clarisse observes the world, asks questions, notices details. She likes having

actual conversations with other people. She gives him presents of flowers and

chestnuts and autumn leaves.

He

can’t stop thinking about Clarisse, and that makes him start questioning

everything. And once he starts questioning, it isn’t long before everything

starts falling apart. He realizes that his life is empty. He and his wife never

have conversations; she spends all day watching empty dramas on their wall-size

TVs. And when she’s not watching TV, she listens to constant chatter on her

earbud radios, or takes sleeping pills to conk out.

And

he realizes that all this time he has been burning books without even once

reading any of them, to see if they really are as bad as he’s been led to

believe.

So

at his next book burning call, he slips one into his shirt and takes it home. And

then we discover that he’s been doing that almost unconsciously, blindly, for

quite a while.

And

then Clarisse and her entire societal-norm-flouting family mysteriously

disappear from their house.

And

then Montag goes to a call where they are burning the books hidden in the home of

an elderly woman. She is so distraught by them burning her library that she

throws herself on the fire, and he sees her burn to death before his eyes.

| Oscar Werner as Guy Montag in François Truffaut's somewhat plot-altered, but still Bradbury-approved, film version of Fahrenheit 451 |

~

When

I was in sixth grade, a family friend gave me an anthology of Ray Bradbury’s short

stories. I didn’t have any idea who Bradbury was, but I gobbled the book up. Stories

like A Sound of Thunder, Skeleton, and There Will Come Soft Rains were vivid and disturbing and

delightful; I read them over and over again. When I was able to get my hands on

more of his short stories and a copy of The

Martian Chronicles, I gobbled those up, too.

But

I only first read Fahrenheit 451 because

I had to, for a class assignment in junior high school. I liked it all right; I

enjoyed the story and I was surprised that my teacher would assign such a

modern and readable book. But it didn’t make much of a deep philosophical

impact on me at the time. I don’t think I had enough life context to give it

meaning.

When

I was in college and had gained a little more experience and knowledge of world

history, I read Fahrenheit 451 again.

It had a lot more power for me than it had before. It resonated with my outrage

at real-life book burnings and at people who wanted to proscribe what other

people could read and think simply because it bothered them. I saw it as an

artful illustration of the evilness and impossibility of thought censorship.

And

now, many years later, I have read it a third time. My life is completely

different now than it was when I was in either junior high school or college. I have a full-time job that

eats up the bulk of my week. I have family obligations and stresses and much

less leisure time to fit in all the projects and travel and socializing I want

to do. In the evenings I often sit on the couch and watch TV and let my mind go

blank. And this book spoke to me now in a different way than it

had before: this time, it made me think about how I am constantly running, fending

off demands on my attention, and how I allow the self-centeredness and lack of content in

the media around me to use up my time and mental energy so that I don’t take the

time to observe, listen, create, and think.

Fahrenheit 451 is, itself, the kind of book that the firemen were protecting society against. It is melancholic,

unresolved, and requiring of deep thought. It is fiction, but it forces us to take

a hard look at our reality. And that’s exactly what makes it so important.

I

think one of the marks of a great book is that it has richness enough to mean

many things to many people, and all of them can be true. This is certainly true

of Fahrenheit 451. It carries many

messages: about the destructiveness of censorship, about the need to step

back and be in the world, about the

need to relate to other people, about the need to be curious, about coping with

clashing inputs to come up with your own standards of what is right. To do all

this and to do it in the form of a well-written and entertaining story is beyond

impressive.

Friday, May 16, 2014

Book Review: Accelerando

Charles

Stross

2005

Awards:

Locus

Nominations: Hugo

Nominations: Hugo

Rating:

★ ★ – – –

I’m

angry at Charles Stross. I’m angry at him for making me like Apocalypse Codex, thereby gearing me up

to be excited to read this book, and then having it turn out to be so annoying.

The

story is set a couple hundred years in the future, just at the time when our computers

are reaching the point of singularity. The combination of processors and

circuits that make up our technological network is becoming alive; able to

think, adapt, and grow.

Our

computing power has also progressed to the point where we can spin off virtual,

aware, thinking copies of ourselves. This lets us go off and do ten different

things at once (all in virtual, networked environments, of course), bring our

copies all back together and reintegrate their separate experiences into our

main host body.

Oh,

and, also, we have been able to make contact with an intelligent alien race by

sending virtual copies of ourselves off into space and setting up a virtual

meeting space in a common location with them.

In

order to provide enough energy to support all this processing, unfortunately,

we have to use our own solar system as a power source. We are dismantling the

planets and asteroids, starting from Mercury and moving outwards, turning all

the organic material into a ring of metallic, rocky debris surrounding the sun,

each piece of which turns the sun’s light into energy. When we are finally

finished, we will be left with no planets but only concentric rings of solar-radiation-conducting

chunks of rock, acting as a massive power source for all our virtual

environments. Stross calls this a “Matrioshka Brain,” and says it can keep us

all alive—virtually, of course, in virtual environments—practically forever,

after our “fleshbodies” are gone.

Into

this situation steps our cast of characters. Main character #1 is Manfred Macx,

an “Artificial Intelligence emancipationist.” He somehow makes his living by

giving away information—variously and vaguely described by Stross as ideas, innovations,

property rights, patents, future information, and paradigm shifts—for free. He

does it for the principle of the thing, as sort of a white-hat hacker or an

open-source activist. The grateful people to whom he gives these things often

give him things in return in a sort of low-pressure, optional barter

transaction.

Then

there is main character #2, Manfred’s daughter Amber Macx. She is a

technological whiz and a charismatic leader with a penchant for drama. She (or

a virtual copy of her) spends a lot of her time flying around the solar system

in a ship the size of a Coke can, holding audiences in virtual environments.

She is the one who pioneered contact with the extraterrestrials, and she is one

of the first to realize that the dismantling of the solar system might be a

problem.

There

are also others, of course; Manfred’s second wife, Annette, who wears

mirror-shaded glasses and wearable computing in what must be a nod to

Neuromancer, and a sentient robotic cat, Aineko, who is a little odd, in that

he is a male calico.

Together

this motley crew—under Amber’s leadership—must figure out what to do to save

humanity (if, indeed, it warrants saving).

Accelerando uses the

premise of unlimited technological possibilities to avoid having to craft a

coherent universe for its characters. The concept of virtual reality allows Stross

to suspend rules arbitrarily, breaking them and then re-applying them as needed

in order to make the plot move forward. It inserts total virtualization into

real life in a completely unfettered way that ends up feeling aimless and

meaningless. And silly.

On

the one hand, anything goes. One crew member on Amber’s ship likes to go around

as a velociraptor, for some reason, and her stepmother chooses to appear as an

orangutan for a while. Amber likes to decorate her virtual spaceship variously

as a fifteenth-century castle or an ancient Persian market. Avatars and objects

appear and execute complicated behavioral patterns with a gesture, a wave of

the hand, with no apparent programming necessary by anyone, either in the

present or the past.

But,

at the same time, there are odd restrictions in this otherwise do-anything

virtual reality world. At one point, for example, Amber goes virtually to Venus

to talk to a virtual avatar of a Venusian entity in a virtual Venusian

environment. But she still has to limit her time there, because her avatar won’t survive in that environment

for long. Why is that? Why would an avatar need oxygen or heat shielding?

Why

did this bother me? I don’t think it’s because it’s a little surrealistic. Roger

Zelazny’s writing can be very surreal, and is a thing of beauty. I also don’t

think it’s because part of it takes place in a virtual environment per se. Snow Crash and Neuromancer

both did that too. But their virtual worlds held together dramatically because they

existed according to rules that were internally consistent.

I

think it is because it feels flippant. It seems too sloppy, too much like

magic. Boom! That guy is now a lobster. Isn’t that funny? It is like a piece of

abstract art that you’ve been told is a work of genius, but you have a sneaking

suspicion that it’s actually been painted by a child.

It

also makes me feel like he’s making the story up as he goes along. The plot

wanders wildly from side to side and yanks you around. Key plot points are left

extremely vaguely explained, from Manfred’s profession to the Matrioshka Brain.

In the end, it made me not really care if the solar system was saved or not.

Friday, June 28, 2013

Book Review: Rainbows End

Vernor

Vinge

2006

Awards:

Hugo, Locus

Rating:

★ ★ – – –

I

find myself extremely unmotivated to write this review. It is neither a book I feel

good enough to recommend, nor a book I hated enough to slam.

I

did end up liking this book better than Vinge's A Fire upon the Deep or A Deepness in the Sky. Mainly because it was shorter than either of them. And also because the plot was a touch tighter and less randomly free-associational. Rainbows End is set in the near future, and starts out with several semi-coherent separate

plots which inevitably converge at the climax of the book.

I

did end up liking this book better than Vinge's A Fire upon the Deep or A Deepness in the Sky. Mainly because it was shorter than either of them. And also because the plot was a touch tighter and less randomly free-associational. Rainbows End is set in the near future, and starts out with several semi-coherent separate

plots which inevitably converge at the climax of the book.

One

story line follows the recovery of an elderly man, Robert Gu, from Alzheimer’s

disease. Robert had been a brilliant, world-famous poet until he developed Alzheimer’s

and descended slowly into dementia. Then, one day, at the beginning of the book, he wakes up again to find that

modern medicine has cured him and given him a brand-new

start on life. He goes back to school to learn all of the things that he missed

out on during his decades of decline, including how to use the ubiquitous “wearables”—wearable computers that let you issue commands through gestures and see

feedback displays and virtual images overlaid on the real world through contact

lenses.

Another

story line is about high-level international internet security personnel trying

to track down a hacker-terrorist somewhere in the net who they think is designing a dangerous

semi-biological,/semi-technological virus. Their problems multiply when it

turns out there is not just one hacker-terrorist but at least two, one of whom

may be one of them, and one of whom may be an artificial

intelligence, and who are sometimes working together and sometimes working at

cross-purposes.

And

still another story line is about a group of UCSD professors who are trying to

prevent the shredding of all the books in the main library on campus.

All

of the story lines eventually come together around Robert Gu. Robert lives with his son and

daughter-in-law; they are both Marines working for Homeland Security and are

trying to track down the hacker-terrorist(s). Several of Robert’s former

colleagues are involved in the subversive anti-shredding movement. And several

of Robert’s current schoolmates have been recruited—wittingly or unwittingly—to work

for the hacker-terrorist(s). It all comes to a head

when there is a big save-the-library-books riot at the UCSD campus, which the

hacker-terrorists have arranged to cover up their nefarious viral activities.

Robert

Gu is a more interesting main character than the similarly-aged

protagonists in Vinge’s other books. He is a touch more well-developed; he has a unique back story and understandable,

powerful motivations for his actions.

But the strength of Gu's character is unable to overcome Vinge's flippant, careless storytelling style. Vinge is, as ever, too clever for his own good. Zillions of new technological ideas spew out all book long like water from a lawn sprinkler. But he doesn’t develop their function enough so that you care about, identify with, or remember most of them. Some are pulled magically out of his hat (or, in one case, from a scientist’s bag) for the first time at key moments when they are needed to solve some immediate problem. And most are left behind, unresolved and partially used, falling forgotten into the background when the next page is turned.

Many of Vinge's ideas are evocative of earlier works by other authors. Rainbows End draws, of course, from William Gibson's virtual realities and artificial intelligences. But there are also echoes of Neil Stephenson in the avatars that populate the net and the digitally dynamic nanotech "paper," not to mention the appearance of hundreds of thousands of mice as a key plot point. And white westerners lapsing into Asian languages always reminds me of Philip K. Dick.

But the strength of Gu's character is unable to overcome Vinge's flippant, careless storytelling style. Vinge is, as ever, too clever for his own good. Zillions of new technological ideas spew out all book long like water from a lawn sprinkler. But he doesn’t develop their function enough so that you care about, identify with, or remember most of them. Some are pulled magically out of his hat (or, in one case, from a scientist’s bag) for the first time at key moments when they are needed to solve some immediate problem. And most are left behind, unresolved and partially used, falling forgotten into the background when the next page is turned.

Many of Vinge's ideas are evocative of earlier works by other authors. Rainbows End draws, of course, from William Gibson's virtual realities and artificial intelligences. But there are also echoes of Neil Stephenson in the avatars that populate the net and the digitally dynamic nanotech "paper," not to mention the appearance of hundreds of thousands of mice as a key plot point. And white westerners lapsing into Asian languages always reminds me of Philip K. Dick.

I did

like Vinge's idea of wearable computing (even if it is somewhat derivative of Neuromancer). But I found it

preposterous that his characters could be doing so many things at once with their

wearable computers without being completely catatonic. Vinge has them occasionally looking distracted for maybe

a moment while they’re researching, reading, or silent messaging. But given how

in real life people are unable to walk in a straight line while having a conversation on their

smartphones, I don't think there's any way humans could be doing all that simultaneously

without being totally zoned out and inattentive of the real world.

And

his occasional descents into silliness come at just the wrong frequency and

strike just the wrong note. They aren’t consistent enough to be Douglas Adams,

and aren’t clever enough to be Connie Willis.

Friday, January 25, 2013

Book Review: Hyperion

Dan

Simmons

SPOILER ALERT

The

most powerful political entity in the universe of Hyperion is the Hegemony, which governs a large number of technologically

advanced member planets. Hegemony worlds are connected by faster-than-light

communication and space travel, as well as instantaneous Star-Trek-transporter-like

portals called “farcasters.” This planetary information and transportation

network is referred to as the “WorldWeb.”

The

most powerful political entity in the universe of Hyperion is the Hegemony, which governs a large number of technologically

advanced member planets. Hegemony worlds are connected by faster-than-light

communication and space travel, as well as instantaneous Star-Trek-transporter-like

portals called “farcasters.” This planetary information and transportation

network is referred to as the “WorldWeb.”

As

the book opens, fleets of battleships from the Hegemony and their primary enemies,

the “Ousters,” are headed to Hyperion to battle for control of the planet.

Knowing that Hyperion will be changed forever no matter who wins, the Church of

the Shrike invites seven people to go on what will probably be the final

pilgrimage to the Time Tombs. The novel tells the story of the pilgrims’

journey to the Tombs and intertwines that main story with their individual back stories, which they

tell each other on the way.

Simmons

is aware of his predecessors, and overtly (and respectfully) draws from their earlier

works. But, at the same time, he also creates some really inventive new elements

for each of the sub-stories in his novel. He thinks up new technologies, both large

and small, for war and entertainment and commerce. His worlds often have striking

scenery (like the Sea of Grass on Hyperion) and original and sometimes oddball biota

(like the migrating, floating islands of Maui-Covenant).

1989

Awards:

Hugo, Locus

Rating:

★ ★ ★

★ –

The Story

Hyperion is the

first book in what eventually became a four-part series called the Hyperion Cantos. It is set in the distant future, at a time when humans have settled far and wide throughout the galaxy.

The

most powerful political entity in the universe of Hyperion is the Hegemony, which governs a large number of technologically

advanced member planets. Hegemony worlds are connected by faster-than-light

communication and space travel, as well as instantaneous Star-Trek-transporter-like

portals called “farcasters.” This planetary information and transportation

network is referred to as the “WorldWeb.”

The

most powerful political entity in the universe of Hyperion is the Hegemony, which governs a large number of technologically

advanced member planets. Hegemony worlds are connected by faster-than-light

communication and space travel, as well as instantaneous Star-Trek-transporter-like

portals called “farcasters.” This planetary information and transportation

network is referred to as the “WorldWeb.”

Outside

the Hegemony are a number of remote, inhabited planets that aren’t connected to

the others by farcaster. Even with FTL travel it still takes

years to get to them, which discourages visitors, colonists, and commerce. Some

of the inhabitants of these planets like it this way.

One

of these remote planets is called Hyperion. Hyperion is home only to a small

number of indigenous people, archaeologists, exiles, and missionaries. It is sparsely

populated not only because it is physically distant and technologically isolated,

but also because it is the home of the Shrike: a terrifyingly huge homicidal monster,

basically humanoid in form except that it has four arms and metallic spikes

poking out all over its body.

Most

people are terrified of the Shrike. Some have formed a religion around it and

the places it frequents—particularly the mysterious Time Tombs of Hyperion.

The

strange thing is that it turns out that none of the pilgrims are members of

the Shrike church. And they come from a weird range of professions: priest, poet,

scholar, soldier, detective, ship captain, diplomat. But their stories reveal

that they each have a strong reason for being on the pilgrimage and for confronting

the Shrike.

Respect for the Past

Hyperion is consciously

modeled on the Canterbury Tales, Chaucer’s

novel about pilgrims telling stories to each other on the way to Canterbury

Cathedral, which I have to admit I didn’t really like when I read it in school.

But the tales told by the Hyperion pilgrims are really good. They are varied

and unique, and several are told in radically different styles, reflecting the

very different voices of their tellers.

The

scholar’s story, for example, is very sad. His beloved only daughter was an

accomplished archaeologist working on her dream site in the Time Tombs on

Hyperion. But during an accident in the Tombs she caught an affliction that

caused her to age backwards. The scholar has had to watch her regress painfully

from brilliant scientist back to childhood; by the time he is picked to go on

the pilgrimage, she is an infant. His story moves all the other pilgrims, and

he uses it to raise bigger existential questions, almost like a bible lesson or

philosophical exercise.

This

stands in contrast to the detective’s story, which is like a gritty noir

mystery except with the gender roles reversed. The scotch-drinking (female)

detective is world-wise and tough, ogling the beautiful (male) client who walks

into her office one day to hire her. Her story is almost a mini Neuromancer, a

cyber-piracy adventure involving artificial intelligence and cyber-cowboys and

a heady trip through the virtual “DataSphere.” It pays deliberate homage mainly

to Raymond Chandler and William Gibson, but also to Philip K. Dick, Aldus Huxley,

and Arthur Conan Doyle.

Creativity and Foresight for the Future

And,

unlike Vernor Vinge, he really explores his ideas, fully integrates them into his story, and then wraps them up nicely before moving on to the next, so

you don’t feel like you’re being blasted with an undeveloped-idea firehose.

One

of my favorite of Simmons’ environmental inventions is the flame forest of

Hyperion. This forest is full of tall

mushroom-shaped trees that, under the proper conditions, become giant lightning

rods bursting with lethal zaps of electricity, turning everything in their

entire area into smoldering cinders. This deadly forest is used to great effect

both at the beginning and the end of the priest’s tale.

Simmons also appears to be pretty foresighted in certain areas. In

the poet’s story, for example, he experiences the sense of hopelessness and ennui that can

come from being constantly plugged in to political minutiae through intrusive, omnipresent

communication technology that we didn't even have yet in 1989.

The

poet is also disappointed when the TechnoCore (the collection of artificial

intelligences in the Hegemony) loves his latest epic poem, but doesn’t buy any

copies, and his agent points out that “copyright means nothing when dealing

with silicon.” She says that the first AI who read it probably downloaded it

and shared it instantly with all the others via the WorldWeb network. I don’t know how

many other people were thinking about this on such a big scale back then.

And

keep in mind, also, that Simmons was writing about his “WorldWeb” network of cyber-connected

planets and computers at a time when the World Wide Web was barely a glimmer in

Tim Berners-Lee’s eye.

The Down Side

There

are some down sides to this novel, unfortunately. For one thing, there is only

one female character of any importance, and she is deliberately modeled after male predecessors. The other women who show up in the book are dominatrices, character-less wives, or idealized lovers waiting patiently for their men to return.

Simmons’ writing also has a tendency to get overly long, romantic,

dreamy, and obscure. I’ll have to admit I skipped some of the more overwritten

parts and that I found the consul’s story—one of the most important ones for

the Shrike story—pretty confusing.

But

I still think I want to read the next one (Fall

of Hyperion) to find out what happens to some of the characters. And to see

what more new cool landscapes and life forms Simmons will invent.

Friday, January 4, 2013

Book Review: Neuromancer

William Gibson

William Gibson1984

Awards: Nebula, Hugo, Philip K. Dick

Rating: ★ ★ ★ – –

I am of two minds about this book.

On the one hand, I very much appreciate it. It is the very best in cyberpunk writing. It was groundbreaking and radical when it came out in 1984, and it still reads like a fresh, contemporary story today.

Gibson is great at taking abstract technical concepts like computer viruses, hacking, ROM constructs, and artificial intelligence and describing them so that you can picture them; so that they seem physically real. He does this for many things that were brand-new and almost inconceivable to most people at the time.

He also coined the term “cyberspace” and used the word “matrix” to describe the virtual environment of the internet, even though the internet didn’t really exist fully yet for most people.

Neuromancer is fast-paced and slick. People go swinging around the matrix at the speed of light and also zip around physical space very quickly as well; it’s no big deal to go from one end of the BAMA (Boston-Atlanta Metropolitan Axis) to the other, even just for dinner.

Its characters have talents and body modifications adapted to this new environment. The protagonist, Case, is a cyber cowboy with an enhanced nervous system whose trade involves jacking into the matrix and hacking around stealing information. Case meets up with a number of colorful people, including Molly, a sort of mercenary who has retractable razor blades implanted under her fingernails (like Wolverine, although Wolverine actually came first) and high-tech mirrored lenses embedded over her eyes that give her access to all kinds of real-time information.

On the other hand, I don’t really like this world. It’s hostile. Everyone seems high on something most of the time. No one can trust anyone else and no one is sure if they’re on the right side. You can't ever be sure if what you’re looking at is real or a hologram. No one has a home; Case just rents various “coffins” (cheap tiny hotel spaces) to spend the night.

I don’t like Case or Molly or any of the people they run into (with the possible exception of Wintermute, who is actually an artificial intelligence and not a person).

I also don’t understand anyone’s motivation for doing what they’re doing (with, again, the exception of Wintermute).

The premise of the story is that Case used to be one of the best cyber cowboys out there, but he made the mistake of stealing a piece of information from an employer, who then fried his nervous system so he couldn’t jack into the matrix anymore. When a mysterious new employer needs someone to do the most dangerous, complex hacking job ever, they hire him to do it and are willing to pay for the extremely expensive operations required to fix him. Yet I didn’t think that Case ever really proved why he was so good (like, for example, Ender Wiggin proved over and over).

Case develops a romantic relationship with Molly, who has been hired by the same mysterious employer to be the muscle on the hack job. But they seem to get together just because they’re in the same place at the same time, not because they really are interested in each other.

Neil Stephenson’s novel Snow Crash, which came out in 1992, draws a lot from Neuromancer, both in its atmosphere and in its story line. But I liked the characters and the world of Snow Crash much more.

An earlier version of this review originally appeared on Cheeze Blog.

Friday, August 10, 2012

Book Review: Ender's Game

1985

Awards: Nebula, Hugo

Rating: ★ ★ ★ – –

SPOILER ALERT

Before I read Ender’s Game for the first time, I had heard a lot of hype from others about how life-changing this book was for them. It didn’t live up to the lofty expectations that the hype had set up and I was disappointed.

I read it again recently, though, and this second time I think I was able to appreciate the book much better for what it is.

The story is set in the future, when we on Earth are nearing the end of an 80-year break in an interstellar war against another species, the Buggers. The Buggers’ original two invasions were brutal and all of humanity is united in preparing to defend Earth against the expected Third Invasion. Governments have begun genetically engineering children to be soldiers in the coming war; they run them through a series of tests when they are little to see if they will be good candidates for Battle School (when they are elementary-school age) and then Command School (when they are teenagers). In school, they run the children through battle simulation after battle simulation, teaching them how to fight and kill.

The main character in the book is Andrew “Ender” Wiggin, a six-year old military genius (who is good at many other things as well). He is lonely at Battle School, ostracized and sometimes hated by many of the older students who are threatened by his skill. They do everything from not eating with him at meals to trying to kill him in the hallways. But he is so good that he still rises rapidly through the ranks at Battle School, leading first small groups and then whole battalions of his fellow students, entering Command School several years early.

Ender enjoys what he does. He is creative and adaptable. He learns his opponents’ patterns quickly and exploits them. The problem is that he doesn’t like to kill. And the more successful he becomes, the more agonized he gets inside about what he is doing. He knows he is being used as a tool and it makes him miserable.

What he doesn’t realize until it is too late is that the humans don’t just want to defend themselves against a Third Invasion – they want to completely annihilate the Buggers and their home world. And that at some point, the battles he is fighting have changed from simulations to real encounters with the enemy that he is commanding by remote control.

He does, finally, lead the human forces to victory over the Buggers, with huge loss of life. When he finds out what he has done he goes through a profound breakdown and decides to completely redirect his life and honor the memory of those he has killed.

It is a very good story and Ender is a very likeable character. I definitely identified with his loneliness and I liked the way he was always able to think his way into succeeding against huge odds. I just had a couple problems with the book.

One was that the ending seemed too abrupt. It was very quick. I guess I thought that Ender would eventually be on the actual battlefield himself, or that we would actually meet a Bugger, and when neither of those things happened, it was a bit unsatisfying.

The other was the more minor story of what was going on back home while Ender was at school. Ender’s brother Peter and sister Valentine are geniuses in their own rights, but Peter was too aggressive and Valentine too pacifistic to make good military leaders. Left out, they begin writing columns and editorials in global political nets, widening divisions between political factions (mainly between America and Russia). I didn’t really get into their story as I did Ender’s.

After reading Ender’s Game, I read the sequel, Speaker for the Dead. I just loved it. It was moving and complex and I enjoyed seeing what Ender had become as an adult, after he had turned away from the military. Later I read that Orson Scott Card originally meant both stories to be in the same book, but that when he got into it, he realized that it was too much and he should split off what was then just a backstory about Ender’s youth into its own book, which would then be a set up for Speaker. If that is indeed what he intended, it totally worked for me.

Awards: Nebula, Hugo

Rating: ★ ★ ★ – –

SPOILER ALERT

Before I read Ender’s Game for the first time, I had heard a lot of hype from others about how life-changing this book was for them. It didn’t live up to the lofty expectations that the hype had set up and I was disappointed.

I read it again recently, though, and this second time I think I was able to appreciate the book much better for what it is.

The story is set in the future, when we on Earth are nearing the end of an 80-year break in an interstellar war against another species, the Buggers. The Buggers’ original two invasions were brutal and all of humanity is united in preparing to defend Earth against the expected Third Invasion. Governments have begun genetically engineering children to be soldiers in the coming war; they run them through a series of tests when they are little to see if they will be good candidates for Battle School (when they are elementary-school age) and then Command School (when they are teenagers). In school, they run the children through battle simulation after battle simulation, teaching them how to fight and kill.

The main character in the book is Andrew “Ender” Wiggin, a six-year old military genius (who is good at many other things as well). He is lonely at Battle School, ostracized and sometimes hated by many of the older students who are threatened by his skill. They do everything from not eating with him at meals to trying to kill him in the hallways. But he is so good that he still rises rapidly through the ranks at Battle School, leading first small groups and then whole battalions of his fellow students, entering Command School several years early.

Ender enjoys what he does. He is creative and adaptable. He learns his opponents’ patterns quickly and exploits them. The problem is that he doesn’t like to kill. And the more successful he becomes, the more agonized he gets inside about what he is doing. He knows he is being used as a tool and it makes him miserable.

What he doesn’t realize until it is too late is that the humans don’t just want to defend themselves against a Third Invasion – they want to completely annihilate the Buggers and their home world. And that at some point, the battles he is fighting have changed from simulations to real encounters with the enemy that he is commanding by remote control.

He does, finally, lead the human forces to victory over the Buggers, with huge loss of life. When he finds out what he has done he goes through a profound breakdown and decides to completely redirect his life and honor the memory of those he has killed.

It is a very good story and Ender is a very likeable character. I definitely identified with his loneliness and I liked the way he was always able to think his way into succeeding against huge odds. I just had a couple problems with the book.

One was that the ending seemed too abrupt. It was very quick. I guess I thought that Ender would eventually be on the actual battlefield himself, or that we would actually meet a Bugger, and when neither of those things happened, it was a bit unsatisfying.

The other was the more minor story of what was going on back home while Ender was at school. Ender’s brother Peter and sister Valentine are geniuses in their own rights, but Peter was too aggressive and Valentine too pacifistic to make good military leaders. Left out, they begin writing columns and editorials in global political nets, widening divisions between political factions (mainly between America and Russia). I didn’t really get into their story as I did Ender’s.

After reading Ender’s Game, I read the sequel, Speaker for the Dead. I just loved it. It was moving and complex and I enjoyed seeing what Ender had become as an adult, after he had turned away from the military. Later I read that Orson Scott Card originally meant both stories to be in the same book, but that when he got into it, he realized that it was too much and he should split off what was then just a backstory about Ender’s youth into its own book, which would then be a set up for Speaker. If that is indeed what he intended, it totally worked for me.

This review originally appeared on Cheeze Blog.

Friday, July 27, 2012

Book Review: The Diamond Age

Neal Stephenson

1995

Awards: Hugo, Locus

Nominations: Nebula

Rating: ★ ★ ★ ★ ★

Neal Stephenson is one of my favorite sci-fi writers and I’m disappointed that with all the funny, rich, and prescient books he has written, I only get to write about one of them here.

I was introduced to Stephenson by a co-worker who suggested that I start with this book rather than the somewhat more famous Snow Crash. About ten pages in, I was hooked.

The opening chapter drops you bang into a new world on the outskirts of Shanghai fifty years or so in the future. You don’t understand any of the lingo or the technology or much of what is going on at first. But (as in A Clockwork Orange or anything by Shakespeare) you learn quickly by immersion.

The society of The Diamond Age is technologically advanced but in many ways socially backward. Almost everybody belongs to a “phyle,” which is a sort of tribe or clan. Phyles are heavily class-segregated; the phyle you are in determines where you live, whether your neighborhood is polluted and crime-filled or not, how much education you receive as a child, and so on.

People who don’t belong to any phyle are called “thetes.” They live in a sort of demilitarized zone between phyle enclaves. They are outcasts who must survive by their wits and often by turning to lives of servitude or crime.

Some phyles have strength because of sheer numbers or sheer ruthlessness. Others have strength because they possess skills that others are willing to pay for. The richest and most powerful of these is the New Atlantis phyle, which is home to nearly all the “artifexes” (designers & programmers) of the nanotechnology that the world depends on. New Atlantis enclaves are on artificially extruded hills high above the poorer sea-level phyles, where the air is cleaner and their houses are easier to defend.

New Atlantans have adopted the lifestyle and mores of late-19th century Victorians – deeply repressed emotions; convoluted social etiquette; sweeping skirts and parasols for women; snuffboxes and waistcoats for men. But all of these affectations are supported by, and in some cases overtly combined with, the incredibly advanced nanotechnology that pervades everything.

Nanosites are responsible for purifying water and air and for performing most medicine. Neighborhoods are protected by grids of hovering nano-pods that can either be passive information-gatherers or defensive weapons. And the coolest thing (I thought at the time I read it) is that newspapers and books are no longer made of paper and print; they are now made of nano-paper, thin layers of nanosites sandwiched between mediatronic screens that can display a universe full of multimedia presentations at the request of the reader. (And to think it only took Apple 15 years after this book came out to come up with the iPad.)

To try to sum up the plot quickly (a tremendous injustice):

Lord Alexander Chung-Sik Finkel-McGraw, a powerful man in New Atlantis, sees that the crushing overprotectivity of his clan is causing their children to grow up without either creativity or common sense, and that this will eventually lead to their downfall. He hires a brilliant artifex, John Percival Hackworth, to build an intelligent, interactive book, a book he calls the Young Lady’s Illustrated Primer, for his granddaughter. The book will supplement and subvert the Victorian educational system; it is designed to teach a child to think creatively and to solve real problems, instead of the theoretical ones presented in schools.

Finkel-McGraw contracts with Hackworth to build one book, under top secret conditions, and makes him swear to destroy the compiled code so no one can ever build another one.

Hackworth builds the book but does not, however, destroy the code. He sneaks it out of his laboratory and takes it to a seedy neighborhood in Shanghai where he pays Dr. X, an off-network power broker with a matter compiler, to compile a second copy for his own daughter.