Clifford D. Simak

1981

Nominations: Hugo

Rating: ★ ★ ★ – –

I like Clifford Simak’s novels a lot, and I think part of the reason might be because he started out as a journalist. His writing is clear and accessible without being simplistic. His main characters tend to be thoughtful loners who still care about other people. And he is able to use his kind, thoughtful little stories to raise big questions about big topics, without being didactic about it.

Project Pope’s big questions all revolve around the reconciliation of faith with science in the search for truth. And as a framework for these questions, Simak invents a paradoxical thing: a society of robots trying to build a religion.

The actual plot is a little peculiar. There are certainly moments of violence, danger, and even at least one murder. But his main characters are generally trying to do the right things even if they mess up sometimes. And even though they face threat, they face it with kindness and an earnest interest in puzzling out the solution.

---

The book starts with a pretty darned exciting scene. On the remote planet of Gutshot, doctor Jason Tennyson has just run afoul of the law for the crime of having his boss, a city bigwig, happen to die on his watch. In a daring escape, he stows away on the next vessel leaving Gutshot’s spaceport, which turns out to be headed to the planet End of Nothing.

As the name would suggest, End of Nothing is the most remote planet in the known galaxy. And, for that reason, it was chosen by a group of cast-off robots from Earth to be the site of their project to create a new robot Vatican, complete with a robot Pope.

On Earth, robots were forbidden from developing their own religion So the ones who founded End of Nothing are extremely skittish about visitors and publicity, and this has piqued the interest of the only other human passenger on Tennyson’s ship, reporter Jill Roberts. Having received no response to her many written requests for information from the new Vatican, she is headed there in person to get some answers.

When they arrive at the End of Nothing, one of the human residents has had a severe accident, and the only human doctor there has recently died. So the robots, who don’t ask too many questions about legality anyway, ask Tennyson to stay and be their new doctor. He assents, not having too many other options. And, in an attempt to make things more palatable for Tennyson and to co-opt Roberts, they offer her a position as Vatican historian.

Roberts and Tennyson learn that the new Vatican employs a select group of semi-telepathic humans as sort of cosmic scouts; these people are able to travel in their minds to other worlds, and they do so, searching one world after another for Heaven.

They do this in service of the new Pope, who is convinced that religion can be derived from science. He believes that if he is able to search wide enough and far enough, he will discover the physical location of Heaven, and then he will be able to have a scientific basis for his faith.

But there is an underground faction of robots that believe that this is the wrong way to approach it; that faith must come first, and science must come after. This is the fundamental tension of Project Pope: the conflict between robots who believe faith must be derived from science, and those who believe science must be derived from faith. And, unbeknownst to our main characters or the Pope, both sides have adherents that are willing to make deadly cases for their beliefs.

While this dispute is simmering, Tennyson strikes up a friendship with Decker, a cabin-dwelling loner who has been on End of Nothing for most of his life, and Decker’s close companion, a sparkly trans-dimensional being named Whisperer that can also itself travel telepathically to other worlds. Whisperer takes Tennyson and Roberts on several journeys to meet the various wacky inhabitants of different worlds, and there they make the acquaintance of a group of aliens that look like giant dice that can print mathematical equations on their surfaces.

Eventually, one of the Vatican’s scouts finds Heaven--or is at least convinced that she has. She suffers a nervous breakdown as a result, but Whisperer is able to read enough of her mind to trace the scout’s journey back to the world she thought was Heaven, and to bring Tennyson and Roberts there.

What they discover there is not actually Heaven but instead a strange city world peopled by a motley group of aliens--including a duplicate of Decker, a furry alien shaped like a haystack, and an octopus-being that constantly plops up and down making a sound like liver being slapped on a countertop. One of these creatures turns out to be one of the faith-firsters, and it is determined to destroy Heaven, and possibly the rest of the universe along with it, by blowing itself up. There is a simultaneously tense and funny climactic scene in which Whisperer, Tennyson, and Roberts are able to avert catastrophe by bringing in their equation-surface-dice friends, and everybody lives, if not happily ever after, at least to see another day, albeit with lingering questions about God, the Devil, Heaven, and the nature of the universe.

---

In the introduction to her novel

The Left Hand of Darkness, Ursula LeGuin explained that the great thing about descriptive science fiction is that each piece is a “thought-experiment.” She said:

In reading a novel, any novel, we have to know perfectly well that the whole thing is nonsense, and then, while reading, believe every word of it. Finally, when we're done with it, we may find - if it's a good novel - that we're a bit different from what we were before we read it, that we have been changed a little, as if by having met a new face, crossed a street we never crossed before. But it's very hard to say just what we learned, how we were changed.

The artist deals with what cannot be said in words. The artist whose medium is fiction does this in words. The novelist says in words what cannot be said in words.

To some extent, Simak does this with

Project Pope. It is not the world’s greatest piece of science fiction. But, at the end, if he has done his job for you, you wind up having enjoyed a somewhat quirky story about robots and aliens, while also simultaneously engaging your mind on questions that might not otherwise be easy to conceptualize. Is it better, he asks, to search for universal scientific truths, and to allow religious belief to develop from that? Or to grab hold of a religion--to search for Heaven--first, and then to use that idea of truth to frame your search for scientific knowledge?

Each reader is going to have to answer that question for themselves, of course. Simak provides the framework that enables you to think about it, but does not (and cannot) provide an answer. As Tennyson tells the robot Pope: if you asked a hundred humans whether faith should come out of knowledge or knowledge out of faith, you’d get all sorts of different answers, and any of them may be right.

But, being humans, we still want to ask the question. “We grasp for knowledge;” says Simak, through the thoughts of his main character. “Panting, we cling desperately to what we snare. We work endlessly to arrive at that final answer, or perhaps many final answers which turn out not to be final answers but lead on to some other fact or factor that may not be final, either. And yet we try, we cannot give up trying, for as an intelligence we are committed to the quest.”

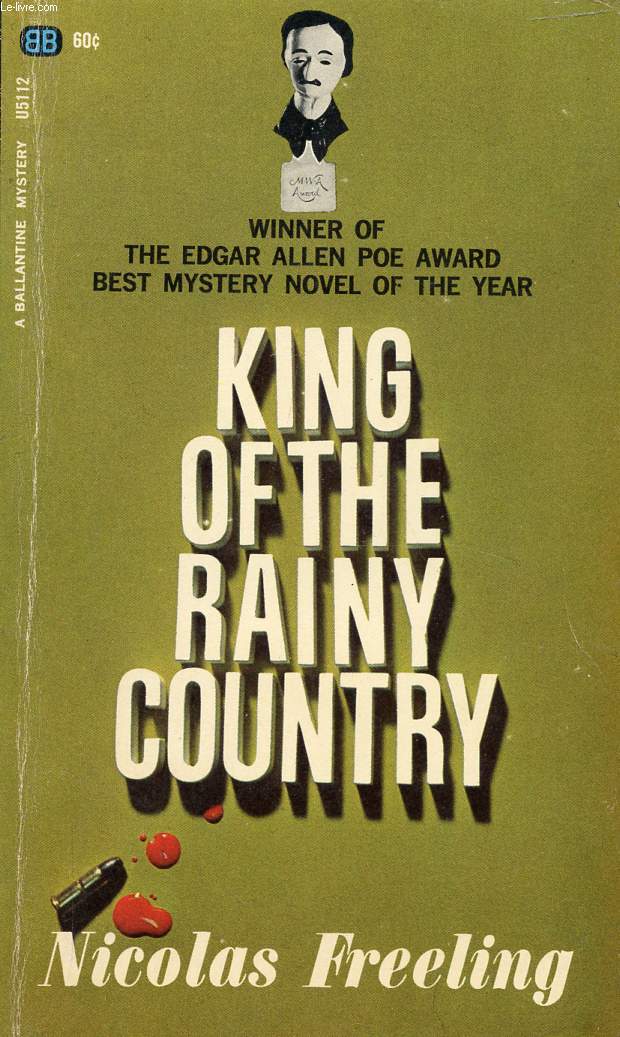

ook

makes it look like a trashy piece of pulp fiction. It has a drawing of

the main character, handsome private detective Murray Kirk, being leaned

on by a lovely young lady who is half out of her satin dinner dress and

matching heels. A block of text next to the pair describes the book as

“a story about the special world of a private detective.”

ook

makes it look like a trashy piece of pulp fiction. It has a drawing of

the main character, handsome private detective Murray Kirk, being leaned

on by a lovely young lady who is half out of her satin dinner dress and

matching heels. A block of text next to the pair describes the book as

“a story about the special world of a private detective.” This book is not a stereotypical murder mystery with a lot of drama and

gore. As advertised, it follows the progress of a crime very closely and

realistically, from the murder to the trial of the chief suspects. You

experience the investigation from the point of view of several people

trying to figure out what happened – reporters, policemen, and lawyers.

Sometimes they get information through good detective work, and

sometimes they get it accidentally. You find out what they know as soon

as they know it, and you put the story together with them.

This book is not a stereotypical murder mystery with a lot of drama and

gore. As advertised, it follows the progress of a crime very closely and

realistically, from the murder to the trial of the chief suspects. You

experience the investigation from the point of view of several people

trying to figure out what happened – reporters, policemen, and lawyers.

Sometimes they get information through good detective work, and

sometimes they get it accidentally. You find out what they know as soon

as they know it, and you put the story together with them. This

murder mystery takes place in Los Angeles in the 1950s. A wealthy,

antisocial woman, Helen Clarvoe, starts getting weird, threatening phone

calls from an old acquaintance. The calls scare her, so she hires her

family’s financial advisor, Mr. Blackshear, to try to find out who is

calling her and why. This leads Mr. Blackshear on a nice investigation

in which he uncovers all sorts of interesting secrets about Helen’s past

and the other members of her family, and during which one of the people

he is investigating commits suicide and another is murdered.

This

murder mystery takes place in Los Angeles in the 1950s. A wealthy,

antisocial woman, Helen Clarvoe, starts getting weird, threatening phone

calls from an old acquaintance. The calls scare her, so she hires her

family’s financial advisor, Mr. Blackshear, to try to find out who is

calling her and why. This leads Mr. Blackshear on a nice investigation

in which he uncovers all sorts of interesting secrets about Helen’s past

and the other members of her family, and during which one of the people

he is investigating commits suicide and another is murdered.