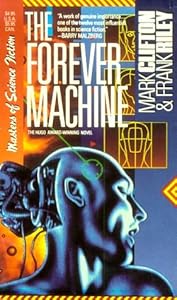

1957

Awards: Hugo

Rating: ★ ★ ★ ★ –

This book is really abstract and way out there. I think much of it was beyond me. But what I did get I really enjoyed.

This book is really abstract and way out there. I think much of it was beyond me. But what I did get I really enjoyed.The Big Time’s main premise is that the time in which we live is actually an enclosed environment, and that there is a zone surrounding us, a gray misty space outside of and separate from our time, where other beings live. These other beings can come and go into and out of our time at will, plopping onto our world at any time in our past or future that they choose.

Two groups of these beings, which we never actually see but which are called “Spiders” and “Snakes” by the main characters, are fighting a massive war against each other, using our time as their battlefield. This war involves them: (a) recruiting recently-dead people to be soldiers and support staff for their side, (b) resurrecting the ones who agree to sign up, and (c) sending the resurrected soldiers into different eras of our time to fight the forces of the other side.

Through this process, the Spider and Snake soldiers have managed to screw up history in all kinds of ways, like by changing the outcomes of important battles in ancient Rome and assassinating key people during World War II who had never been assassinated before.

The entire book takes place in the misty realm outside of our time, in a sort of behind-the-lines R&R spot for Spider soldiers. The spot is populated by resurrected formerly-dead people who serve as entertainers, prostitutes, counselors, and doctors for the troops. These “ghosts” are pretty satisfied with how things are going until one visiting soldier decides to mutiny against the Spiders, breaks the connection to real time so they’re floating lost in the timeless zone, and then starts the countdown on a portable atomic bomb.

The main character who narrates the story is one of the prostitute/counselor/entertainers. She is very appealing; she has a laid-back attitude and uses a lot of slang, and, although she is our guide to this weird world, she doesn’t feel the need to explain a heck of a lot. I also really liked the variety of the other characters. Since the Spiders can recruit from any place and time they want to, their support staff and soldiers are necessarily from all different countries and all different eras, including the future.

An earlier version of this review originally appeared on Cheeze Blog.

This is one of the last books in Asimov’s

This is one of the last books in Asimov’s  This

book was only available in the Young Adult section of my library. And,

after reading it, I can see why; this is definitely a book for

teenagers.

This

book was only available in the Young Adult section of my library. And,

after reading it, I can see why; this is definitely a book for

teenagers.